It’s All About That Space

I’m sorry, were you bored with italics? Good—that’s why busy plant biologists hire editors like us to take care of the picky details. Let’s talk about something that is arguably more interesting—in fact, it has started Twitter feuds. That’s right: spaces (or the lack thereof)!

Do put a space between the number and the unit, thus: 15 mM NaCl, not 15mM.

However, for symbols, the rule changes: most publications have no space between the number and the % or ° symbols: so, 15%, not 15 % and 25°C, not 25 °C. Note that this exception itself has exceptions; for example, the U.S. Government Printing Office uses no space for degrees of arc, but does use a space for degrees of temperature, so 180° angle, but 25 °C. So, the style guide for the publication should take precedence and consistency matters.

We recommend that you do leave a space between allele names in multiple mutants. Unless organism or journal style guidelines dictate otherwise, don’t jam allele names together for multiple mutants—it gets hard to tell where one allele ends and the next one begins. So, if you are looking at pin1-1 pin3-2 pin5-5 triple mutants, please don’t go all pin1-1pin3-2pin5-5wheredoesitallendmakeitstop??? on us, please.

This is a bit controversial (think Twitter wars), but we suggest you leave ONLY one space after the period at the end of a sentence. If you are old-school, feel like your sentences are tailgating, or like to drive copyeditors nuts, you can choose to leave two spaces after the period—but make sure to do this consistently, and don’t be surprised if that extra space disappears by the time your manuscript gets published. If you don’t believe us and need more convincing, check out this post from Grammar Girl Mignon Fogarty.

Mind your compound words. Sometimes spaces between words disappear from the English language, making one word where once we had two. Don’t put a space in wavelength, rainforest, sunlight, or ultraviolet. Crosstalk, too—unless your daughter is crabby and you don’t want to hear any more of her cross talk. Use “green house” if you are writing about the color of the paint, but “greenhouse” if you are growing plants under glass.

Some compound words are trickier than others:

-

- Leave a space in wild type (or add a hyphen as needed: wild-type plants).

-

- A system might show feedback (noun, one word), but expression of one transcription factor feeds back on another (verb, two words).

- Downregulate and upregulate give our authors lots of trouble and usage varies in the literature. For example, Google Scholar has 145,000 entries for “upregulate” and 265,000 for “up-regulate”, but we prefer the one-word version. Check journal style by using a keyword search and, as always, be consistent throughout your paper.

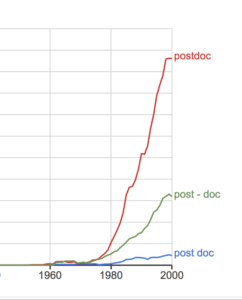

For a quick check of word usage, you can also track it over time with the Google Ngram viewer. Enter different variants of your words, separated by commas, and see which usage is more common.

Enter different variants of your words, separated by commas, and see which usage is more common.

[In case you were wondering what people called “postdocs” before 1980, the term “serf” appears to have lost usage in a big way at that time. Coincidence?]

Finally, for spacing, if you have doubts, you can use a keyword search to check journal style. Either way, be consistent! Just like an artist considers negative space, authors (and editors!) must consider the spaces in between, to make figures look well-composed and readable, and to make text look neat, consistent, and easy to read.

Got any great or horrible examples of spacing? Want to start a Twitter war about one space vs. two after the period? (Just kidding.) Got a question? Get in touch with us here, and follow us on Twitter @PlantEditors and @PeridotSciComm.